July has been a good month for us to visit Shetland, but we have always set off with more than one eye on the weather. It has been fairly kind on each of our three trips – on no occasion have we spent a single day looking at the wrong side of the window pane. I imagine it can be a bit grim when the weather closes in. I’m reminded of a trip to Orkney I made when a student in London. I had travelled north on a Sleeper train which was much delayed and I missed my flights. I was waiting at Kirkwall airport to begin the final leg of my journey, a flight to Westray. A chap brushing up in the terminal building asked me where I was going. He considered my response: “Aye”, he said, “it’s a grey, lonely place.” There were days when the weather seemed to roll in like a curtain blocking out all the light and I’ve always dreaded a similar experience on Shetland. I guess we’ve had a few near misses.

The ferry takes a long time and I’m very glad that we’ve been able to fly there. Sumburgh Airport is really close to the Sumburgh Hotel, and to the RSPB Sumburgh Head reserve. The reserve visitor centre turned up in an episode of the BBC series Shetland in which it was pretending to be an hotel (Jimmy Perez met one of his many hotties there for an intimate aperitif) – it made quite an attractive one.

The coastal path starts in the hotel grounds and makes its way towards the Head, avoiding the road and offering great views of the headland which rears up to the south. The reserve has dry stone wall boundaries – just as well really. The cliffs are precipitous and it would have been easy to get carried away mid-photography and fall hundreds of feet to the sea, because there was much to see on the cliffs, and at their feet. There were Guillemots, Fulmars and Kittiwakes but the punters had turned out for the Puffins, which were rather conveniently present right at the top of the headland with their feet in the turf.

Our first visit took place in 2017 – this was my first trip to see Puffins, and it was very exciting. But I was a bit anxious – would there be any Puffins there when we visited? I had only seen them on the television and was a little sceptical about their confiding nature. I though we might glimpse them before they flew away or plunged into their burrows, but they were pretty straightforward to photograph. Some posed nicely while others called.

Most visitors to the reserve stayed close to visitor centre and car park; we went slightly further afield and were surprised to find this group atop a wall. We came across Puffins elsewhere on the main island; anywhere with suitable cliffs seemed to hold at least a small population of breeding birds. We also saw rafts of Puffins on the sea a couple of times (no pictures of the appropriate standard, alas) – these were likely to be fresh birds, not yet ready for breeding, and went about their courtly rituals seemingly oblivious of observers..

All of our visits have taken place around my birthday and its imminence prompts me to make this post. A second stimulus was provided by the BBC’s Your Pictures Scotland in the form of several images of Puffins with Sandeels (mostly from the Isles of May). You’ll have noticed that I don’t have the money shot – a Puffin returning to the nest with a bill-full of food. Not negligence – we never spotted such a bird over three visits, which was a bit of a worry. Puffins were flying out to sea, and back in to the cliffs, so where was the food?

Their main prey is the Sandeel (Scottish waters contain five species). Kittiwakes also favour these small fish and Kittiwakes are not doing well, so how is it going with Sandeels? The RSPB tells us that “Sandeels are disappearing due to dramatic changes in their plankton diet.” Warmer seawater results in many species moving northwards – if this means that the plankton are no longer abundant around our coasts, then the Sandeels, which don’t seem to move too far from where they mature, and need fairly shallow water, don’t get to feed. Sandeels are oily and very nutritious and provide the perfect food to get small seabirds growing quickly. If the Puffins and Kittiwakes can’t find Sandeels within range of their burrows and nests, they are forced to fly further out, or rely on less nutritious fish species. I became interested in this during our 2019 visit when the breeding colony seemed a bit lethargic and not entirely sure what it was about. I wondered if they were failing to find food.

I remembered my interest in this scenario when an e-mail arrived recently from Scottish Greens telling me that “A new consultation to be launched by the Scottish Government will consider proposals to end commercial fishing for sandeels in Scottish waters, a big boost for Scotland’s puffins and other iconic seabirds.” The Scottish government has been interested in ways of curbing this trade for several years: the then Scottish Rural Secretary Mairi Gougeon promised to investigate ways to stop “industrial” sandeel fishing by Danish and Swedish fishing vessels in Scottish waters (ca. 2020).

This e-mail came in just before the news that the Scottish government had scrapped its controversial plans for Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) which appeared on the BBC website on 29th June. I was confused but it seems to be a question of extent. I quote: “As part of the Bute House Agreement – which brought the Scottish Greens into government in a historic power-sharing deal with the SNP – Holyrood ministers had committed to designate at least 10% of Scotland’s seas as HPMAs by 2026. It meant that all forms of fishing including recreational catch and release angling would be prohibited in selected sites. Seaweed harvesting would also be banned, no new marine renewable energy schemes would be allowed and the laying of subsea cables would be restricted. Managed levels of swimming, snorkelling and windsurfing would be allowed.” HPMAs were what the Scottish fishing industry and Fergus Ewing were really unhappy about.

About 37% of Scotland’s seas are already included in Scotland’s Marine Protected Areas (MPA) These areas are managed for the long-term conservation of marine resources, ecosystems services, or cultural heritage, which sounds great. In passing, it would seem more sensible to have basically the same acronym for both situations, modified by a prefix, rather than the messiness of HPMA and MPA. Nevertheless, Sandeels are caught commercially, 94% of the take going to Danish boats according to The Sunday Times (“Puffins starve as Danes grab UK Sandeels”, Jonathan Leake, The Sunday Times, 22nd July 2018) in a slightly Germans-towels-and-sunbeds -nuanced moment. Their oil (Sandeels, not Germans) is extracted, or they are turned into fishmeal for use in agricultural feed, or possibly both. Quite a lot of them are caught – the Danish quota for 2023 allows around 200,000 tonnes to be landed. The Danish fishing industry viewed this quota as “reasonable”, which probably means they’d have accepted considerably less.

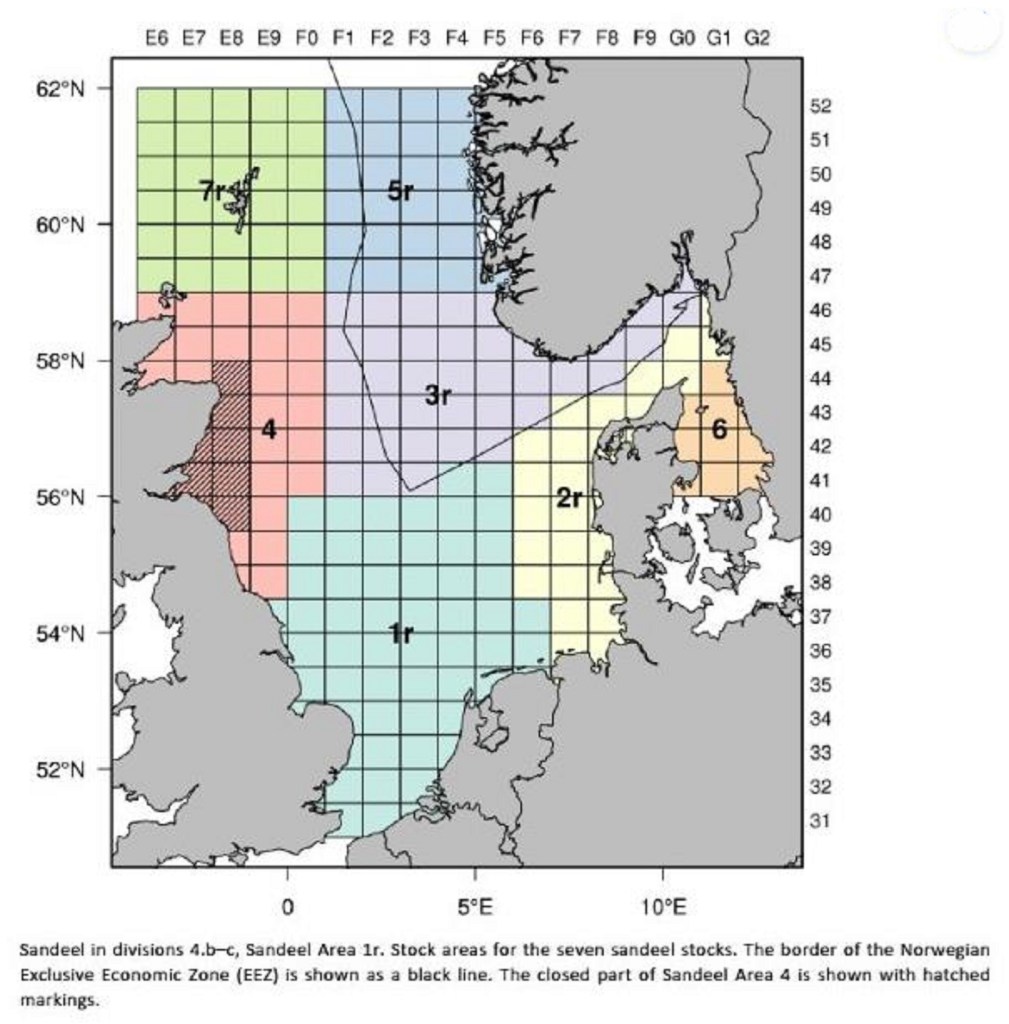

I have lifted this map from the story in The Fishing Daily (which reminds me of that august journal “The Milk Producers’ Weekly Bulletin and Cowkeepers’ Guide“, well known to some of you). The Danish quota for area 7r (Shetland) is zero tonnes; there is a substantial part of area 4 which is closed to sandeel fishing. You would hope that these controls might look after at least some of Scotland’s Puffin and Kittiwake colonies. I mean, if you’re a Puffin hanging in Shetland, it would appear that you have a fair bit of area from which to gather your Sandeels, unless they really have gone from those waters because of the warming sea. There must be plankton around Shetland because there are cetaceans. The Firth of Forth also looks like it has a buffer, unless the Sandeels have moved quite a bit further north into area 4 where they can be fished for.

I’m probably reaching unreasonably optimistic conclusions from this back-of-an-envelope bit of ecology – the RSPB has produced a detailed briefing document in which it sets out a series of measures which might help the seabirds and I will work my way through that in due course and try to understand the problem properly. Puffins certainly travel; there is data from geolocator studies which shows that some long journeys are undertaken.

I hope to return to Shetland in the near future. There is much wildlife to enjoy besides Puffins, and some truly memorable coastal scenery.