The “Life or Death Struggle” sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus summarises rather accurately (from about 1:49) Backwoodman’s negative feelings about many of the nature programmes on the telly. All that resource spent capturing marvellous footage and hiring species experts and what are we treated to? A litany of species X slaughtering species Y is what; most of the Attenborough extravaganzas generally tell the viewer disappointingly little about the marvellous adaptations on display. If Ewan McGregor is involved in the programme, it’s even worse; the body count rises rapidly to levels realised only on one of Begbie’s rampages in Trainspotting. We deserve better! More detail, less uninformative violence, please.

Some Monty Python now seems ridiculously dated but if you can fight your way through the opening, the sketch offers more, with a succinct summary at 2:26 of Backwoodsman’s recent falling out with a large American corporation (the one which shares a name with that of an unburnt brick dried in the sun). This large concern was keen to tell Backwoodsman that his copy of Lightroom, purchased in 2017 from a reputable high street retailer was in fact bootleg software, and that the corporation was about to disable it (it wasn’t and they didn’t, but they seem to think they have). This prompted a search for alternative processing software, which turned up the DxO PhotoLab and DxO PureRAW applications available on a generous 31 day free trial.

Backwoodsman has enjoyed using this software and has now bought licenses for both applications. The PureRAW application improves the RAW files which come off the camera using AI technology, a phrase which has many potential meanings. The application seems to be able to deduce what should be in the grainy RAW file from its sampling of billions of images via neural networks and is, I think, colouring in erroneous or noisy sections of image space with fresh pixels. Image files grow to about three times their original size in consequence. Processing then takes place in the PhotoLab application, which seems quite familiar to a Lightroom user. For a photographer trying to capture bird images, and required to use quite fast shutter speeds, the two-and-a-half stops on offer from PureRAW are very useful compensation for the high ISO or sensitivity settings which go with the rapid exposures and indifferent lighting. In On Photography, Susan Sontag wrote: “The painter constructs, the photographer discloses.” Rather than encroaching on the boundary between the two forms of representation, PureRAW’s AI-driven Pointillism would seem to knock the fence down and plough up the ground.

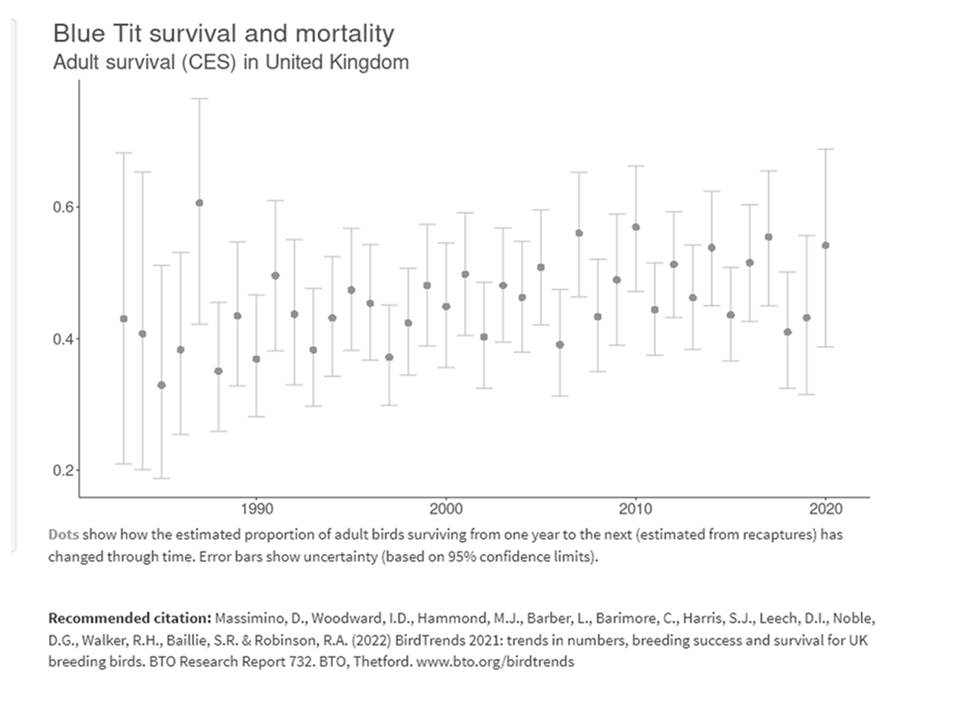

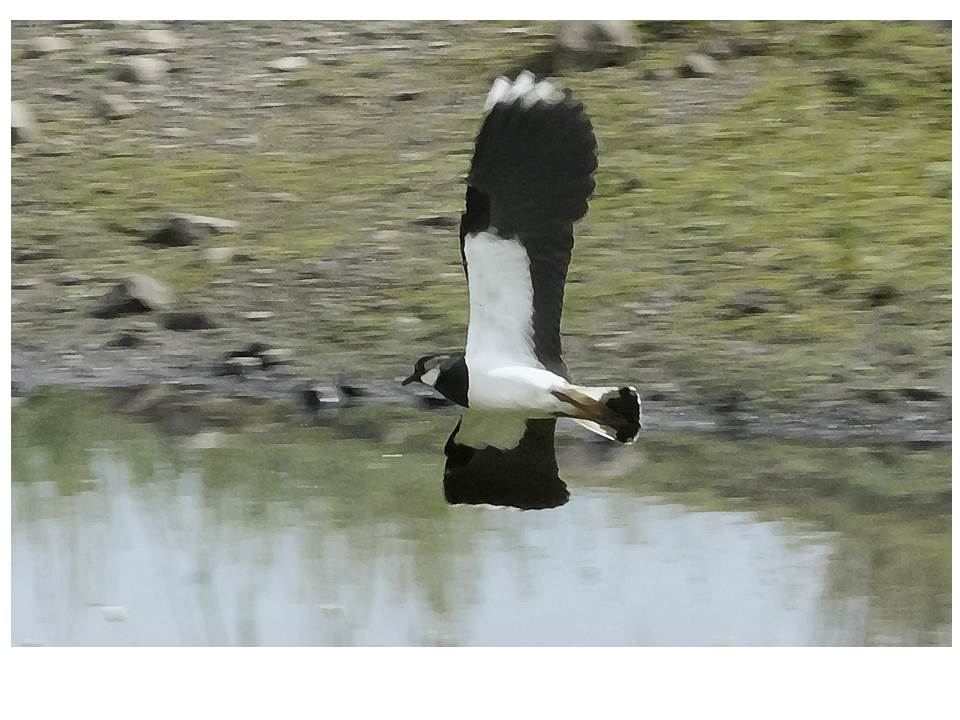

Our visit to Kinneil in early September gave us a good look at some old friends and provided an opportunity to try out the DxO products. While Black-tailed Godwits have already been the subject of a post, we were fortunate to see the birds move from the lagoon where they were resting, to the mud to feed as the tide started to ebb. I used an image of the large resting group to count approximately four hundred birds. As the tide started to ebb, birds started to lift (some Knot went first) and turn towards the sea. They flew right towards us. We were standing in deep shade cast by some Alders and the Godwits landed close by on some fresh mud and started to feed.

I was surprised to hear how vocal they were.

After quite a few minutes, they moved off in a tight flock, settling in anticipation of the tide’s further retreat. I’ve never had images of Godwits in flight before – the black and whites are very dramatic.

Two days after Storm Agnes thrashed the west, I travelled to Troon to see what birds the strong winds had blown to the coast. There was little there alas, apart from some more old friends. A small flock of Turnstones was foraging on the rocks and weed just above South Beach in spectacular light which brought out their colours and textures of the rocky substrate beautifully.

Turnstones formed the subject of one of the early posts but I didn’t have images of this crispness or vibrance, so despite the repetition, I’m sharing them here. After a while, the Turnstones heard something that disturbed them or sensed a change in the wind and took to the wing.

I was also pleased to find Starlings, not only foraging near the Turnstones, but also bathing in a quiet sunny place above the North Beach. Repetition again but I love the brightness and the movement of the birds.

And Monty Python’s finest moment? Well, this takes some beating, not least for the post-goal protests.

Backwoodsman will be back in two weeks with a new species. Until then, he hopes you enjoy these old friends.