You may recognise the view beyond Kinneil Lagoons and towards the Ineos site at Grangemouth on the Firth of Forth. You may also then know that it’s a great place for waterfowl, including Shelduck. As a symbol of our reliance on hydrocarbons, the refinery could also be taken to represent our energy past; Shelduck raise some of the issues arising from one way in which we might meet the energy needs of the future.

The Grangemouth refinery is expected to close and may do so as soon as 2025; the site will instead import refined hydrocarbon products from elsewhere. A BBC article by Douglas Fraser summarises much of the discussion arising from the proposed closure.

Backwoodsman is very fond of Shelduck and was delighted to find them in large numbers on our two recent visits to Kinneil (in September 2023 and January 2024). They were already familiar birds from many visits to Cardross but there were so many birds on the Firth of Forth. Initially, we saw them in rafts heading towards the shore beneath the refinery – following the direction of travel with the camera revealed many more. A rough count in this image reveals around 250 birds in a mere segment of arc of the shore.

The image above was taken on the September visit. Our visits were timed to allow our arrival at the top of the tide; we were hoping to get into position to look out over the mud and view birds as they left the lagoon to feed.

In the view below, there are large groups of Godwits, Lapwing and Redshanks in the distance across the lagoon.

The Shelduck were among the species to oblige and it was pleasing to see them on the wing, and then foraging. The spectacular green flash from the wings is revealed in the Featherbase entry for the species. These feathers are all tucked away in the swimming or walking bird but there is no hiding the sheen of the head and neck, if the light is right.

These wild birds really do not like the camera; at the sight of it, they will stand up and walk away through the sticky mud and then keep their distance.

However, it does seem possible to domesticate them. All the larger images were taken at WWT Martin Mere and Slimbridge reserves where the birds seemed unconcerned by passers-by. It was interesting to read an unsubstantiated allegation of wing-clipping or pinioning of birds at Slimbridge; Backwoodsman has wondered why the birds seem quite so relaxed on the WWT reserves; he attributed their tolerance of visitors to generous feeding. The WWT refuted the allegation of wing-clipping, something of a relief.

Adult males have a conspicuous basal knob on the red bill; the females share the colour but not the protruberance. The second bird in this image seems smaller – Backwoodsman wonders if it is a young bird just starting into adult plumage.

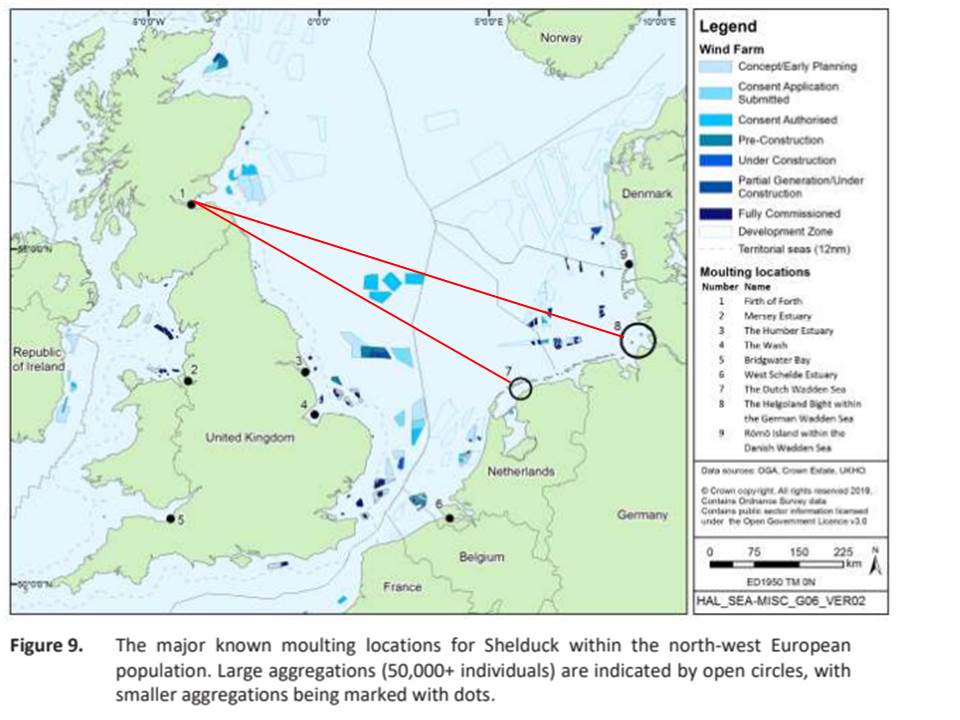

The RSPB book places the breeding season between April and May and then states that “Flight feathers are moulted simultaneously and adults are flightless for 25-31 days between July and October”, adding that “Thousands gather in the Heligoland Bight off the German coast [the north Wadden Sea]. Other moulting areas have recently been discovered on some British estuaries.” BTO reports identify the Mersey estuary and Bridgewater Bay (Somerset) as additional sites with the UK, and the south Wadden Sea as a site across the North Sea. The BTO carried out its own tracking studies and reviewed the literature data to show movement of UK wintering birds to the two Wadden Sea moulting sites. Backwoodsman has taken a graphic from one of the BTO publications and added red lines connecting the Firth of Forth site to the two Wadden Sea moulting areas. Anything blue on the graphic represents current or proposed offshore wind developments. The BTO reports discuss the timing and altitude of flight of Shelduck heading to and from their moulting grounds, attempting to assess the level of hazard and risk to this species posed by offshore wind developments.

To argue for the suspension of offshore wind projects because of potential disruption of Shelduck moult migration would be to try to make a difficult case. Attitudes to offshore wind may have changed since Jenny Turner’s 2012 piece “Among the Turbines” in the LRB and capacity has grown considerably over the intervening decade though there do seem to be issues going forward. In mid-September 2023, The Guardian reported that “… no additional offshore windfarms will go ahead in the UK after the latest government auction. No bids were made in the auction, after the government ignored warnings that offshore schemes were no longer economically viable under the current system.”

Possibly in response to this disappointment, in mid-November 2023, “The government…increased the maximum price for offshore wind projects in its flagship renewables scheme to further cement the UK as a world leader in clean energy.” The auction for 2025 will see if it got its prices right.

Much of the active discussion around UK energy policy seems to deal with pricing rather than methods of generation and efficient storage and deployment. An episode of the BBC programme The Briefing Room illustrates this point. However, there was some interesting news from the Joint European Torus fusion project (based near Oxford) on 8th February 2024, and a short item on the PM programme describing their last and record-breaking fusion burn.

In the fusion reaction, tiny amounts of Deuterium and Tritium (the heavy isotopes of hydrogen) react together in a magnetically-confined plasma (an ionised gas) to make Helium, and releasing huge amounts of energy. There is no long-lived toxic and radioactive waste, nor a weapons angle. I quote from the government press release (see the link above): “In JET’s final deuterium-tritium experiments (DTE3), high fusion power was consistently produced for 5 seconds, resulting in a ground-breaking record of 69 MJ (megajoules) using a mere 0.2 mg (milligrams) of fuel.” According to another source “That’s about as much as burning two kilograms of coal”. A further source said: “It’s an important step … If this energy could be captured and used to power a steam turbine, then the power station output would be about 4 MW, which is not much. I would describe it as a proof of concept, but there is a lot further to go.”

Early days then; there are other projects which use related approaches ongoing elsewhere in the world but JET will now be decommissioned. A strong UK presence in the next project which seeks to take the technology forward (ITER) would seem like a good thing, but the UK seems to be doing its own thing. Backwoodsman really would prefer us to be in there driving projects like this forward, rather than see us building leaky aircraft carriers. There is science money available in current budgets – for example, there would be a bob-or-two going if we stopped doing hubristic particle physics, research into space travel and telescope missions and redeployed the people and the funds to fix clean energy going forward. Oppenheimer managed something like this, though in an entirely destructive context.

Backwoodsman is getting very strong signals that this post is already far too long. Two final disturbing thoughts; one from Laura Kuenssberg who mused “Are the politics of climate change going out of fashion?” at the weekend, and one from Dieter Helm who argues that closing the Grangemouth refinery will not help the UK meet its net zero goals.

Never was duck-fancying so complicated, alas.