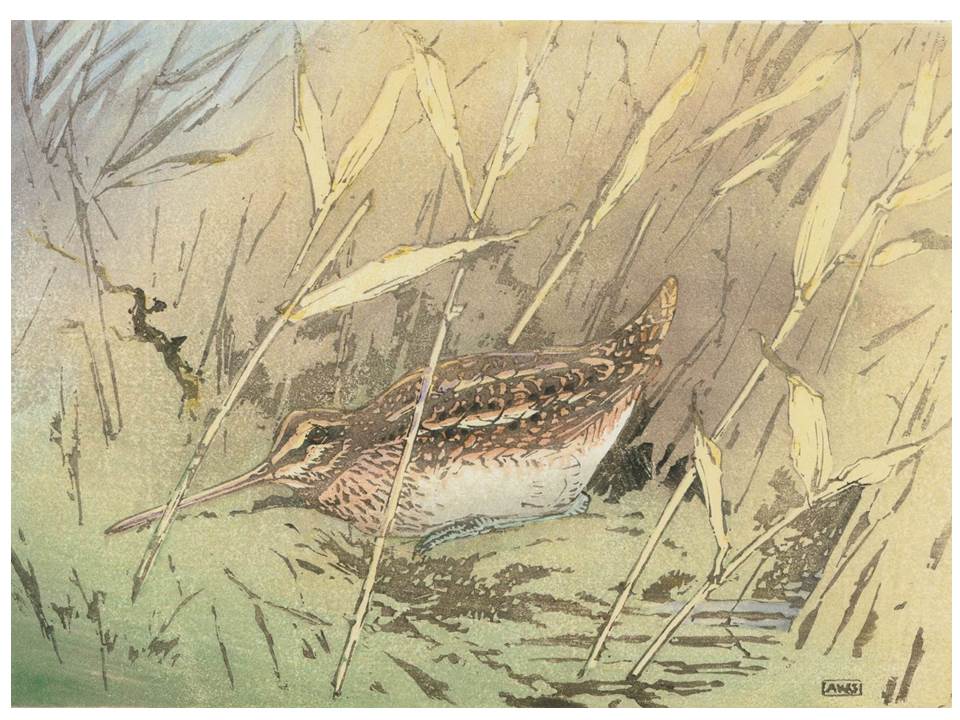

To introduce this species, Backwoodsman offers a fine colour woodcut by Allen William Seaby (please see this one too). The bird and its habitat are drawn and coloured beautifully. Backwoodsman hopes you are getting the impression that this creature may be well camouflaged and therefore quite difficult to see?

Snipe have been on Backwoodsman’s wishlist for a long time but it has just never been the right time to get them in the camera. On a winter day several years ago, Backwoodsman went to RSPB Lochwinnoch with the birdscope but without the camera – together with the necessary tripod, birdscope and camera make for a most uncomfortable pack. Just outside the Visitors Centre window, a scrummage of small waders was underway. A helpful volunteer identified the participants as Snipe. Backwoodsman was transfixed; not only were they a completely mad shape with their long, straight bills but they seemed to be jumping on and over each other in a scene of chaos and frenzy. Fast forward to the Old Racecourse at Irvine; we heard unearthly sounds all around us but could not see any birds; Snipe, said the Merlin App. We were hearing the famous drumming (vide infra). The Stevenston Ponds are reedy and shallow; on a winter visit, a small group of birds exploded from the margin before us and sped away on sharp wings. Our eyes are in by now – the birds are Snipe – but they’ve gone.

How to get onto them with the camera? There is a problem with Snipe; their habit is to conceal themselves while foraging or resting. Baclwoodsman’s RSPB bird book describes them as secretive and the RSPB website has them skulking.

John Clare’s poem to the species (“To the Snipe”) resents the extent to which boys and men with dogs and guns clatter through the natural world disturbing everything and shooting anything slow enough. Of Snipe, he says they are:

“Hiding in spots that never knew his tread

A wild and timid clan

…That from man’s dreaded sight will ever steal

To the most dreary spot”

Backwoodsman behaves a bit like this on Avanti trains so it’s going to be a tough gig to get the images he seeks. Fast forward again to the very end of September 2024 when we visited RSPB Baron’s Haugh. We haven’t usually done very well there – regular readers may remember a slightly disgruntled post from the very beginning of the year (Kingfishers, January 27th) but we decided to give it a punt on a rather grey Saturday. We arrived and from the Causeway Hide, we could see a lot of Lapwings; the autumn season sees a gathering of these beautiful birds at the Haugh.

The hide was busy, and suddenly, so was the sky, as it filled with birds. We looked up and around for raptors but the reason was rather less ethereal. A large atgani chap broke cover on the far side of the Haugh – wearing your camo undies would seem like nugatory effort if you’re going to stand on the birds’ heads.

But there were many Snipe too. At the river, Backwoodsman was able to find the vantage point where the atgani had showed up, and take up a similar forward position, but was able to use the cover much more effectively. There were Snipe right in the foreground, with some attractive dead wood to set them off. There were also Snipe on the wing; the overall impression was that hundreds of birds were present, which was very surprising to Backwoodsman. The book says that Snipe will “gather together in groups and fly in loose flocks called ‘wisps'”.

We get wintering birds in the UK – is it possible that we saw a large group of winter migrants (it was definitely a bit more than a wisp!) just arrived and yet to disperse? The EuroBird Portal does appear to show a lot of movement activity around the end of September.

Baron’s Haugh has undergone a certain amount of remodelling recently, seeking to re-establish a connection between the River Clyde and its natural floodplain. There seemed to be a fair bit of water on the Haugh and it may be that there are more stances for Snipe away from potential predators. The view of the warden (via email) was that, firstly, there were always a lot of birds on the reserve in the winter, and that secondly, they had created quite a few new places where the birds could feel safe from predators (if not entirely from atganis) and stand about in plain sight, rather than skulk.

Backwoodsman found several examples of actions (three links here, one per word) designed to support these and related birds through focused conservation work in the UK.

The Snipe could be confused for a Godwit at extreme range because of the very straight bill, but there can be no mistake once the proportions and plumage can be taken in.

In “To the Snipe”, John Clare wrote:

For here thy bill

Suited by wisdom good

Of rude unseemly length doth delve and drill

The gelid mass for food

The bill – “…of rude unseemly length”; guess he means it strikes him as unusual. Dominic Couzens writes:

“The Snipe’s long, straight bill is the perfect tool for probing deeply into the soft mud, and as a result the Snipe is indeed the champion probe-feeder among waders. It will feed whenever the substrate is not too hard, and it especially favours the edges of pools and puddles. Where the earth or mud is rich it will stand still in one place for some time, making a series of insertions on the spot, leaving behind a semicircle of small holes. And once the bill is in place, the Snipe will often vibrate it a little, and pull it up and down, feeling around in the mud for movement a few centimetres below its feet. The bill is a feat of biological engineering. At the tip it is fitted (as are the bills of most species in this family) with millions of tiny touch-receptors that are wired to a special part of the brain. The receptor organs come in two kinds, one detecting pressure and the other detecting shearing movement. Together they provide the Snipe with an exceptionally fine sense of touch at the bill tip, easily enough to pick up the presence or movement of particles nearby in the mud. The Snipe’s bill also demonstrates another, more unusual trick: it can be opened only at the tip, so that food can be picked up and swallowed without the bird having to remove its bill from the mud. The bill structure is not especially rigid; the component bones and connectors can move relative to one another, an arrangement known as rhynchokinesis. The trick then is mechanical: if the bill is bent slightly at its near end, the bend can be transmitted to the tip such that the rest of the bill remains closed. In this way the Snipe’s bill tip can pinch a worm or insect larva in situ, and the long tongue can then transport the food item up towards the mouth.”

“…the Snipe is indeed the champion probe-feeder among waders.” Just imagine the machinery of evolution slowly but inexorably clicking into place to deliver such exquisite adaptation and performance. Backwoodsman would love to find the primary literature which sets out the taxonomy of the Snipe bill in detail; it must be the stuff of true wonder.

And there is more, again from Couzens: “The bill is not the only unusual anatomical feature of the Snipe; it also has a modified tail. Most waders have 12 tail feathers, but the Snipe has 14 or sometimes more. The very outermost of these are specially stiffened and attached to the body by independent muscles, such that they can be splayed out from the rest of the tail. When a Snipe indulges in one of its rising and plummeting display-flights high in the air, the wind passing by these outermost feathers causes them to vibrate and to make a distinctive buzzing sound (“drumming”), a little like the bleating of a sheep. The sound adds an instrumental dimension to the display, without the bird having to go to the trouble of singing. The sound made by the feathers varies according how susceptible to wear they are; worn-out feathers presumably make a less attractive sound than intact ones.” Here is a a good recording of this remarkable sound. As usual, the Featherbase site allows us to see all the feathers; on the left of the left hand image (IMG241) is a group of 14 feathers which may be the tail array.

John Clare regretted that men found themselves compelled to go boldly and unwelcome into the realm of the Snipe and disturb these beautiful birds (like our atgani). Or possibly, boldly go. Intrusions seem to be much in the news just now with the mounting tide of inane froth about space travel. And now we have Prof Brian Cox at it, being anointed cultural heir to David Attenborough and getting a new series on the BBC. “‘Human race needs to expand beyond Earth,’ says Prof Brian Cox.” Basically, we’ve screwed everything we can out of this planet, so we need to go pillage another one to maintain our ridiculous modes of consumption and waste. Anyone familiar with Attenborough’s elegiac coverage of our fading natural world will find Cox’s brassy rapacity an abrupt and unwelcome change of tone.

Though there could be some potential positives – our finest billionaires heading for the stars in spaceships which then go ‘pop’ (like those rich chumps diving to the Titanic wreck in a submarine which went ‘pop’ implosively), would probably improve the prospects of the species.

It was so pleasing to get anywhere near some Snipe; it would seem unlikely that Backwoodsman will ever get any nearer to one unless some birds show up right outside a quiet hide somewhere. It is tempting to crop tighter and make the images bigger but the quality deteriorates. Perhaps this one is worthwhile; even though there is grain, some of the markings come out nicely and the postures are pleasing. Soon, it will be time for wintering waders at the coast and waterfowl on the lakes, and Backwoodsman hopes, lots of new material.

PS. Some of you may be interested in this petition at Change.org. UK government (DEFRA) is considering permitting the sale of millions of elvers (baby eels) from Gloucester to Russia next spring. Already last year they allowed the export of 1 tonne (3 million individuals) of this critically endangered species. These elvers will be sold to Kaliningrad, a known transit point for the vast smuggling trade in elvers, the most smuggled wildlife in the world by numbers and by value. This all sounds most regrettable.