So, wild mammals again; we had a local canal walk last Sunday. On our way out, we skirted the compound where Amey are based for their repairs to the Woodside viaducts. There was a chap in full camo holding a large cigar in his left hand and a lead in his right. When the creature at the end of the lead emerged from the long grass, it turned out to be a Polecat. A Dundas Hill billy !

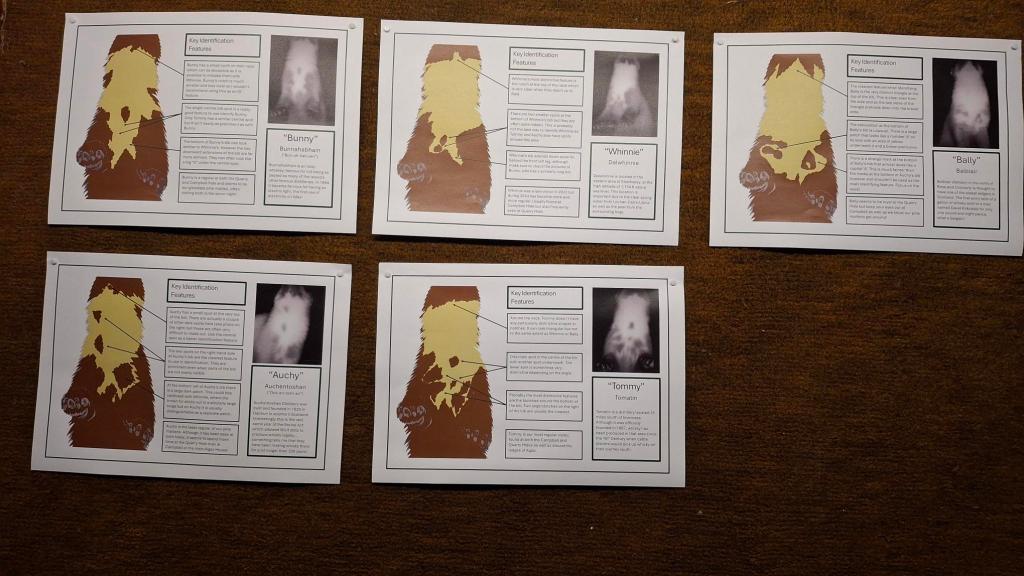

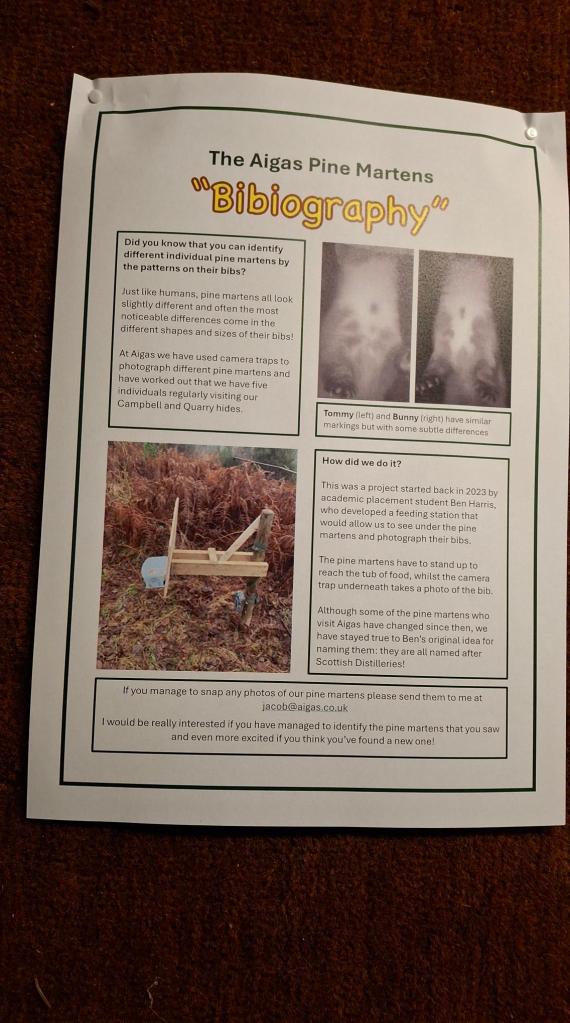

If you read the Red Squirrels post, you should know that the Aigas offer also included Pine Martens. Backwoodsman had never set eyes on one of these creatures before our May trip and was keen to get some pictures. We were offered an after-dinner private trip to the Quarry Hide with one of the wardens, and took up the opportunity with great enthusiasm. Bait was placed, lights were turned on and we took our places in the comfortable hide and waited in stillness and silence. The light fell, various creatures rustled in the grass but of Pine Martens, there were none. After a couple of hours, the vigil was called off and everyone exhaled. When the lights went back on in the hide, we were able to read about the role bib patterns play in identifying individual animals, and the cunning way in which images had been obtained.

The Pinewood Hide had delivered some excellent views of Red Squirrels and we visited it again a couple of days later with the intention of improving Backwoodsman’s stock of Woodpecker images. We baited up and as we scanned the edge of the woodland, something that could only have been a Pine Marten bounded away from the hide and into the bracken in front of us. The mammal book says that the species is “Mainly nocturnal but in summer may forage after dawn and before sunset.” We had not hoped to see one in the bright light of a May lunchtime, and yet…

A small head appeared atop the wall against the dark background of the woodland, viewed the food offer, assessed the level of threat we posed back in the hide, and made its way in for the peanuts.

The animal looked quite relaxed – the camera was clicking away all the time but the Marten neither flinched at the sound, nor looked towards it. The teeth were bared from time to time but it looked more like a reflex associated with chewing or swallowing than a threat.

Once however, the animal seemed to look past our hide and strike a more aggressive posture – could another animal have looked in at this point?

Crisis over and it was time for a look around the area before the trip back to the wall and an exit into the darkness beyond.

We were stunned by what we had just experienced. The images are time-stamped so we know that the Marten had spent twenty-four minutes in our company.

It might be thought vainglorious to say that this set of images was unlikely to be improved upon unless the opportunity arose to photograph two Pine Martens, or an adult and some little ones. However, when offered another after-dinner guided hide visit, we took it up. Our host, Sir John Lister-Kaye, had used one of his short after-dinner speeches to express his displeasure at the selfish actions of a photographer on one of these night-time hide visits, so Backwoodsman was committed to available light and single frame shooting only when we sat waiting in the Campbell Hide. Suddenly, a Pine Marten was with us, crunching peanuts and licking jam from the adventure playground.

So job done, Pine Martens spotted and documented, and what a wonderful opportunity.

Backwoodsman found this in a Natural England blog:

“The pine marten was once widespread and common across Britain but is now rare and recovering. Pine martens are generalist omnivores, eating a wide range of different food species. They predominantly prey on small mammals such as field voles, and this usually consists of up to 50% of their diet. Their diet preference is determined by what is locally most abundant. Predators are a crucial part of a functioning ecosystem. A diverse predator community is expected to naturally limit populations of abundant prey populations. However, pine martens by themselves generally live at low density; a population of one per km2 is considered a high density, and a pair of martens generally need at least 200 ha of suitable woodland.”

So, areas; 200 hectares is 2 km2, which is quite a small area. The Aigas Estate covers 600 acres according to a source (another bewildering unit: an acre is one chain by one furlong, the likes of Mr Rees-Mogg love units like this because no-one can work out how much land his lot actually own!), so that’s 2.4 km2 in sensible units. Five Pine Martens on the property seems quite crowded, but perhaps multiple territories overlap on the Aigas Estate, with individuals making feeding raids and then retreating to somewhere a bit more spacious.

There is a Pine Marten recovery plan which seeks to reintroduce viable populations of these animals into England and Wales without affecting the recovering population in Scotland.

An interesting point from the document: “Recent studies in Ireland…suggested that pine martens may have a negative impact on grey squirrels, with a benefit to red squirrels where they are present and as a result, many organisations and partnerships in Britain are particularly interested in pine marten reintroduction projects for grey squirrel control. However, these are often locally designed initiatives, motivated by local conservation targets, without consideration of how they fit within the wider context of pine marten conservation and of other, similar projects. Reintroductions can offer a powerful conservation tool but when they are motivated and planned at a local scale this may hamper their ability to contribute to the long-term recovery of a species at the larger scale. This is particularly important for species such as the pine marten, which occupy large (ca. 2-30 km2 per individual) home ranges and which, therefore, require suitable landscapes, rather than sites, [Backwoodsman’s italics] in which to establish sufficient territories for a viable population.”

The Aigas Estate has a small but established population of Beavers and breeds Wildcats to support reintroduction projects. Backwoodsman is less excited about these species, or by the others which various rewilding agendas seek to reintroduce, particularly Lynx and Wolves. Some of you may remember the illegal release of Lynx in the Cairngorms earlier this year?

One of the Aigas rangers was enthusing about Lynx: “do you see the reintroduction of Lynx as being an unambiguously good thing?” Backwoodsman asked her. Her answer referred to a “landscape of fear”, in which deer would smell large predators as they forage, and move on smartly without overgrazing, allowing trees to grow back. Deer fencing is no good because Grouse fly into it and maim themselves, so the deer get to roam unchallenged, proliferating far beyond sustainable population densities and grazing everything to extinction. Presumably Wolves would also provide a landscape of fear. They certainly would if they develop a taste for walkers on the West Highland Way. Backwoodsman wonders if pheromone spraying at strategic locations might not be a potential control strategy, as the semiochemicals used by Lynx, for example, seem to be quite well characterised.

According to the BBC story, Lynx became extinct from Britain five hundred to one thousand years ago. Backwoodsman wonders if conserving what we have now should be top priority, rather than reaching back into a past in which people lived and farmed very differently. The rewilding movement is having none of that:

“Nature knows best when it comes to survival and self-governance.

We can give it a helping hand by creating the right conditions – by removing dykes and dams to free up rivers, by reducing active management of wildlife populations, by allowing natural forest regeneration, and by reintroducing species that have disappeared as a result of man’s actions. Then we should step back and let nature manage itself.”

There are four action points in the second paragraph; the first three seem rooted in a practical approach but the fourth is completely unqualified and almost appears an end in itself. Rewilding Britain is the local branch and one of the rewilders celebrated on its website (Dorette Engi) was actually present at Aigas during our visit.

“If Dorette Engi hadn’t read Isabella Tree’s Wilding, which recounts ‘the return of nature to a British farm’, Dayshul Brake [a rewilding cluster] might never have come into being.

With retirement looming, the briskly outspoken psychoanalytic child psychotherapist who grew up in Switzerland, was keen to put her strong Buddhist principles into practice for the planet. Inspired by Wilding, “I thought, perhaps a bit presumptively, ‘OK, I’m going to do that’.” Her presumptuousness extended to booking herself on a rewilding course for landowners at Tree’s Knepp Estate. Presumptuous because, as yet, Dorette didn’t own a single acre. That changed in 2019 when she and her daughter, Eti Meacock, fresh from a permaculture course, and architect son Anthony, bought Broadridge Farm, having scoured the county for suitable sites. “It just felt ideal… It hadn’t been over-fertilised and ‘pesticided’… And it had water. We wanted water”.

Dorette again: “Wilding is experimental. That’s what I like about it. I love the idea of creating a space, and seeing what it needs. Moving forward without following a strict guideline. I really wanted to play.” And “I’m doing a lot by not farming here”, explains Dorette. “The water stays on the land [helping prevent] floods.”

In the area around the Beaver lodge at Aigas, many small trees had been felled, their stumps showing that unmistakable sharpened pencil finish left by Beavers. Quite a bit of chicken wire had been deployed to protect the remaining trees. Backwoodsman overheard a conversation Dorette was holding with another guest. When challenged with the view that the Beavers tended to make quite a mess, Dorette came back with “Well, nature is messy.”

Backwoodsman would contend that nature abounds with symmetries, precision and refinement of adaptation of purpose, in which species of many different types interlock to the benefit of all – if you look at nature and see a mess, maybe you missed the patterns? Perhaps that is a low blow. Nevertheless, where we position ourselves on the continuum from rewilding (anarchic, individual, possibly small scale) to planned large-scale conservation (slow-moving, bureaucratic) will be critical, as governments look hard at big infrastructure projects and planning laws. Public opinion may start to turn against well intentioned conservation efforts, driven away by projects which have slightly slipped their moorings, like the HS2 bat shed.

And of course, big capital is on the way in. Backwoodsman came across this item about wild goats recently.

“A campaign has been launched to protect an ancient herd of wild goats on a moor in the south of Scotland amid an outcry about a cull.The goats roam across Langholm Moor including 11,000 acres (4,450 ha) recently purchased by rewilding company Oxygen Conservation.”

Goats eat trees so their numbers have to fall (it’s the same argument as in deer versus landscape of fear).

Oxygen Conservation say:

“We are growing natural capital at scale

Natural capital is the parts of nature such as forests, water, soils, and oceans that provide benefits to us, from providing food, water, and energy, to removing carbon from the atmosphere, and creating opportunities for recreation. Sadly, despite the importance of natural capital to every part of our society, it is facing a long term and catastrophic decline. Governments have tried and failed to halt this decline, and we believe that it is time for the private sector to start making a positive impact.”

The Langholme Moor site would be a 9 km x 5 km parcel, which must have cost money. Backwoodsman doesn’t have the right sort of vocabulary to understand how purchases on this scale are funded but logically, carbon credits have to be sold to generate, or justify the advancement of, capital, and make a profit for the next round of acquisitions. And of course, there are eco-activities which can generate income – for example, the website shows a group of chumps in wetsuits about to jump into somewhere chilly. No doubt their employer paid handsomely to help them navigate their leadership skills journey going forward.

On April 1st 2025, The Wilderness Society put up a post called “Wolf pack released in the Scottish Highlands”, which was quite funny. There are quite a few green lairds in Scotland now and they’d probably like to play too (pace Dorette). Is this a good future for conservation – rich men, big fences behind which lurk species which were around centuries ago and are now gone? With less favoured species (but possibly quite interesting ones) being tidied away? Backwoodsman feels that the whole rewilding agenda needs much more scrutiny than it is getting just now.

Nevertheless, we were hugely impressed by the Pine Martens and will look forward to seeing them making their way into the West End of Glasgow (ho ho). Though two of our friends did spot one just up the road near Milngavie quite recently. Watch this space!