Backwoodsman feels that there has been little good light for months now. As he emerges blinking from the trees, fetched out by the longer days, he thinks back to a brilliant day just before Christmas when he visited the Claypits LNR on a mission – to find and photograph the Water Rail.

This visit had been thought about for months, ever since we saw a Water Rail on the Forth and Clyde Canal near Stockingfield Junction one Sunday morning. There was no camera to hand so Backwoodsman could only stand and gape as a Water Rail swam across the canal from the towpath side, emerged into the rushes on the far bank and began to forage in full view. All was serene for a few minutes until it was spotted by one of the local Moorhens; hostilities broke out immediately and the Water Rail was pursued down the canal towards the bridge. Our walk continued through the Claypits LNR where we found a couple of birdwatchers with cameras. We lingered too long and they were onto us: “We’ve got a Water Rail, have you seen it?” and so on. We told them about our canal sighting but they so weren’t listening. We left and Backwoodsman resolved to go back on a very bright, cold and midweek day when the reserve might be less contested.

On December 19th 2024, Backwoodsman headed off to the Claypits LNR. The plan was spend an hour or two on the reserve and then jump on a number 7 bus up to Possil Marsh to look for waterfowl. It was a brilliant Thursday morning and absolutely freezing. Backwoodsman arrived at the reserve and crossed paths with a young woman on a mobility scooter; she had seen the bird but not for long enough to get it in focus and capture an image.

Backwoodsman took up a position on the small viewing platform which overlooks the reedy inlet from the canal. The platform looks a bit like a Juliet balcony; anyone standing on it definitely looms, so stillness and silence are essential if anything lurking in the reeds is likely to feel confident enough to emerge for very long. A Grey Heron looked down on Backwoodsman’s folly from its perch across the canal.

Backwoodsman watched; the sun went behind some cloud, the wind came up the canal like a swinging blade and the temperature dropped. Nothing much happened until a long string of bubbles appeared in the small patch of open water Backwoodsman was watching; then there were swirls in the water of the kind that a large Carp would make. A long brown shape with a tail broke surface for a second or two, and was gone. Both Otters and Mink are present in the area. Another time perhaps.

There was a growing clamour as two people in camo and woolly hats came into view. They were shouting, and in seconds, Backwoodsman found himself the filling in a numpty sandwich. Backwoodsman was interrogated; was he from the Clyde Bird Group, or Nature Scot, or the Bearsden Bird Botherers? They were loud, they were moving a lot and they were insufferable. Backwoodsman headed off on a circuit of the reserve.

The numpties had gone when Backwoodsman returned and all was quiet again, save for the calls of a pair of Wrens. They sped through, but not before one had posed attractively in good light.

Then something rather wonderful happened; a female Kingfisher visited, and stayed for quite a long time. These are Backwoodsman’s best images of this species; good light striking the birds really brings the semi-iridescence to life. The bird visited a number of perches; Backwoodsman likes the use it made of the Great Reedmace.

Backwoodsman was very cold by now and started to head for home. While pausing by the inlet for a last look, he was overtaken by a couple of wild-looking chaps hurling whole slices of bread into the inlet. “Aye son”, they shouted, “have you seen the heron?” Backwoodsman was able to tell them that their quarry had been perching in a tree earlier that morning but had flown off. “Son, son”, one shouted, “there’s a wee Robin behind you.”

Backwoodsman turned to see two male Bullfinches in good light, so here is one of them. After a brief discussion of the differences between Bullfinches and Robins, the three of us agreed that it was pure freezing and time for home and we went our separate ways.

So no Water Rails then? Well not on this visit. As it seems unlikely that one will be seen and photographed in north Glasgow by this observer, Backwoodsman will share some images prepared on a visit to Slimbridge.

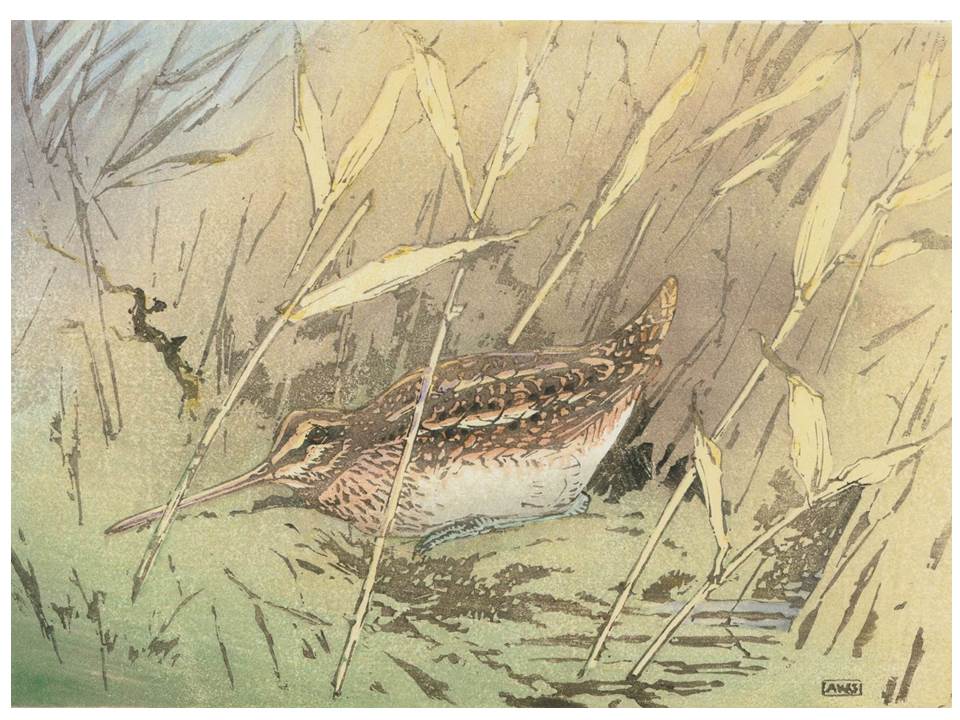

The Water Rail is really very striking, with the upper parts superbly camouflaged for foraging in reedbeds. This video has a bird foraging, and calling or “sharming” as it is known according to the BTO. The Wikipedia article cited at the top of this post is a recommended read: it is a good one.

It is hard to know how things will turn out for this bird on the Claypits LNR. Every time Backwoodsman runs through the Claypits site, he sees someone looming conspicuously by the inlet. Presumably they are after the same bird we saw near Stockingfield Junction, but it would be very exciting to think that there could be two individuals in this area of north Glasgow.