Backwoodsman was fortunate to be booked on a boat trip to the Isle of May, organised by the Scottish Seabird Centre. The trip was a birthday present – thank you, Faye!

The trip took place on a day of brilliant light and across a flat calm sea. We passed by Bass Rock on the way, so it took a while to reach the Isle. Once we arrived at the Isle, we were free to wander, though the importance of staying to the clear paths was stressed by the warden from our boat. And with good reason – almost every part of the grassland seemed to contain a Puffin burrow. Puffins were everywhere, sitting in small groups, or setting off to fish.

There were even Puffins holding Sandeels in their bills, something we had not seen on any of our visits to Sumburgh Head in Shetland.

We headed to the edge of the Isle hoping for some good views down onto cliffs and opportunities to photograph nesting birds. The path took us to some good viewpoints and there, below us, were Kittiwakes and Guillemots in abundance.

Photographing Guillemots can be a bit frustrating, particularly if they are standing on a ledge and incubating eggs – one each, that is. Most birds will be facing the cliff, bill upturned; this group may contain some birds on eggs, though there are no eggs to be seen.

It is worth looking at the rocks on which the birds are standing; “ledge” might overstate the amount of space and stability on offer to some of these birds. As the Scottish Wildlife Trust says:

“Guillemots are fiercely territorial, defending what can be tiny nesting areas. They can show aggressive behaviour towards neighbours and the female may reside on the nest site for several weeks after the male takes the chick out to sea in order to protect the nest site from competitors. In some areas, such as the Isle of May, guillemots have been recorded to return to the nest sites as early as October, most probably to defend high-quality nest sites.”

Backwoodsman also found this:

“A single egg is laid directly onto the bare rock – no nest is made. The mottled egg is pear-shaped (pyriform), and this is a special adaptation so that the egg rolls round in a circle when disturbed rather than off the ledge.”

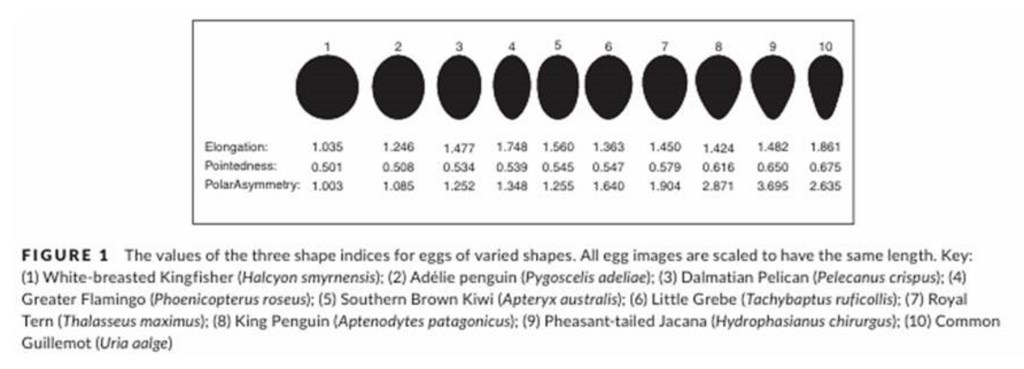

The Guillemot’s pyriform egg is really quite interesting and is much studied. A recent (2020) PhD Thesis by Dr Jamie Edward Thompson from the University of Sheffield entitled “Egg Shape in Birds” discusses the Guillemot’s egg in detail. Thompson points out that:

“[The] Guillemot’s pyriform egg is inherently stable, especially on a sloping ledge, allowing the egg to be more safely manipulated by the parents during incubation and incubation change-overs.”

From photographs, he concludes that the majority of incubating birds are oriented with their heads directed upslope; birds incubating their single eggs, have the blunt end of the egg oriented away from the bird and up the slope. This natural resting position of the egg tends to lift the blunt end up and away from the guano which inevitably carpets the densely crowded breeding ledges. There are many fascinating things in the thesis; one of the publications upon which the thesis is based contains this graphic which shows a whole spectrum of egg shapes, with the pyriform egg at one extreme.

In Chapter 3 of his thesis, Dr Thompson (a student of Tim Birkhead, author of The Most Perfect Thing: the Inside (and Outside) of a Bird’s Egg) writes about Edward Walter Wade (1864–1937), author of The Birds of Bempton Cliffs (1903, 1907). Thompson’s discussion shows Wade to be both an insightful ornithologist and climber of considerable nerve. Unfortunately, he was also an egg collector; page 53 of the thesis shows a remarkable image of Wade, or a fellow nest robber, swinging from a precipitous cliff by a rope.

Once the eggs have hatched, there are chicks. We were able to observe this group from the path close to the cliff top; there was space enough for the birds to be relaxed, and for the photographer to be confident about his footing.

One of the wardens walked by and suggested that the chicks were not too far from launching themselves from the cliff to begin their seagoing lives. Backwoodsman photographed this young Guillemot in September at Aberlady some years earlier.

Birds which are not incubating, and are perhaps waiting to go out fishing, show a bit more of themselves: the chocolate brown head and the yellow inside of the bill respond to strong sunshine.

The birds form rafts on the sea, and individuals will sometimes be sufficiently relaxed to allow close approach by a vessel.

The SWT also comment:

“Many North Atlantic and Arctic guillemots may display a variation in their summer plumage, displaying a striking narrow white spectacle around the eye and white line along the furrow behind the eye. This is not a distinct subspecies, but an alternate colouring that becomes more common the farther north the birds breed.”

It is estimated that approaching one million pairs breed in UK waters. The Forth Islands population is relatively modest in comparison with that based on other sites. Furthermore:

“…geolocation tracking data from common guillemots [was used] to show that they use fixed and individual-specific migration strategies, i.e. individuals go to the same wintering areas in successive years, showing fidelity to geographical sites. They point out that while this behaviour allows individual guillemots to become familiar with their chosen winter home, it represents a constraint in the context of rapidly changing environments. Guillemots may not be able to adjust their migration strategy as conditions change, for example as a consequence of depletion of forage fish stocks in their chosen wintering area, or impacts of climate change on forage fish distribution.”

It remains to be seen what impact the recently approved Berwick Bank development, potentially “the world’s largest offshore wind farm”, will have on the Forth Islands Guillemot population.

Backwoodsman will look forward to his next opportunity to visit the marvellous reserve that is the Isle of May.