Mr Baldwin, the Head Porter at the college to which I belonged while studying for my PhD, had a memorable turn of phrase. I came across Mr Baldwin one morning in the Middle Combination Room, working his way through the pigeon holes into which postgraduate mail was delivered. He wished me a good morning and informed me that he was checking up on some of his backwoodsmen. Finishing a PhD could take a long time in Cambridge in the nineteen eighties and students would vanish from college for years at a time. I liked the application of the term; I don’t think that he meant that the subjects of his inquiry were necessarily uncouth or rustic, but rather that they were rarely in attendance, like certain peers at the House of Lords. I filed the term away for future use. This Backwoodsman has been back in the trees for a while, looking after his stills. Here are some more stills which he wishes to share.

Recent activity on the cage feeder in our window has prompted this post, but alas, the feeder is not in a position which allows good photographs to be taken of the eight Blue Tits which regularly mob it and strip it of its payload of RSPB Super Suet Bars. However, we do have a Birch sapling close to one of our windows, and it is a favoured perch for Blue Tits throughout the year, unsurprisingly, as it between our two feeding stations. In addition to the Super Suet Bars (saturated fat, peanut flower, ground mealworms), they have access to Sunflower hearts (polyunsaturated fat, Vitamin E or α-tocopherol) at the second station. The Tits snatch one or two seeds from under the noses of the goldfinch posse, and take them back to the Birch, where they pin a seed beneath a foot and eat.

Our household view of bird feeding is fairly simple-minded – small birds in particular stand a good chance of starving in the colder months when the seeds and the invertebrates have gone, therefore we should feed them to try to carry them over from one year to the next. Our finch population shifts ca. 300g of Sunflower hearts every day so we are regular purchasers from Pets at Home (that came out as Pest at Home when first I typed it) and the RSPB. We also feed throughout the summer months; we reason that the adult birds will be worn out from incubating and rearing young and will need an instant hit of something nutritious, and the fledglings will need to get off to a good start independent of the availability of grubs.

“Killing with kindness: Does widespread generalised provisioning of wildlife help or hinder biodiversity conservation efforts?“, a 2021 paper from Shutt and Lees, presents a chastening perspective. We are clearly guilty of “trying to help ‘[our]’ wildlife, both for the sake of the wildlife and the pleasure value of wildlife interaction” as Shutt and Lees have it. The paper was picked up by Victoria Gill from the BBC and featured on the Inside Science podcast (at 11:42) – much of the discourse is about the competition between Blue and Great Tits (ubiquitous and a bit extra), and Marsh and Willow Tits (being pushed around and in decline), not a conflict we are able to witness in the absence of the two less competitive species from our area.

While we are clearly sentimental fools, at least our offer is nutritionally balanced. Plummer et al. looked at the effects of three different feeding regimes (unfed versus fat versus fat with Vitamin E) on a Blue Tit population. Here is a chunk from their conclusions: “The findings of this study highlight some potential mechanisms by which impacts of winter feeding may be carried-over to influence events in the subsequent breeding season. To our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence of a carry-over effect of winter food supplementation on the phenotypic condition of wild birds during breeding. The findings also strongly suggest that winter supplementary feeding can alter the phenotypic structure of wild bird populations. The provision of vitamin E appears to have helped to alleviate physiological trade-offs, such that individuals in poor phenotypic condition in the lead up to winter had improved survival and/or a capacity to reach a condition threshold necessary to reproduce during the subsequent breeding season. Furthermore, the opposing impacts of provisioning fat alone compared to fat-plus-vitamin E on physiological condition suggest that negative carry-over effects of winter feeding may be the consequence of a fat-rich, unbalanced diet, as has previously been hypothesized. This is particularly relevant given the substantial variation that exists in commercially available fat products; from high-quality foods enriched with antioxidant-rich nuts and seeds, to low-quality foods bulked out with nutrient-poor fillers such as wheat husks or ash. These findings, therefore, stress the importance of considering the nutritional composition of supplementary food sources and suggest that more research is required to determine how supplementary feeding may contribute to population size trajectories.” I guess they’ll let us off, considering our a nutritionally-balanced offering.

A British Trust for Ornithology research team recently asked the question “Declines in invertebrates and birds – could they be linked by climate change?” concluding that “Our ability to understand these impacts is hampered by a lack of extensive long-term monitoring data for many invertebrates, and invertebrate data collected at scales that can be related to bird populations. We call for collaboration between entomologists and ornithologists, both non-vocational and professional, to support new empirical research and long-term monitoring initiatives to better link changes in insect populations and birds to inform future decision-making. This will be particularly important to understand likely future increasing climate change pressures on birds.” Let’s hope that all gets done. Backwoodsman would suggest that the disappearance of increasing amounts of suburban land under decking, astroturf and concrete, and councils’ tendencies to tidy habitat out of existence may also have influences on bird populations by removing their food sources entirely. I guess we’ll carry on feeding while we can.

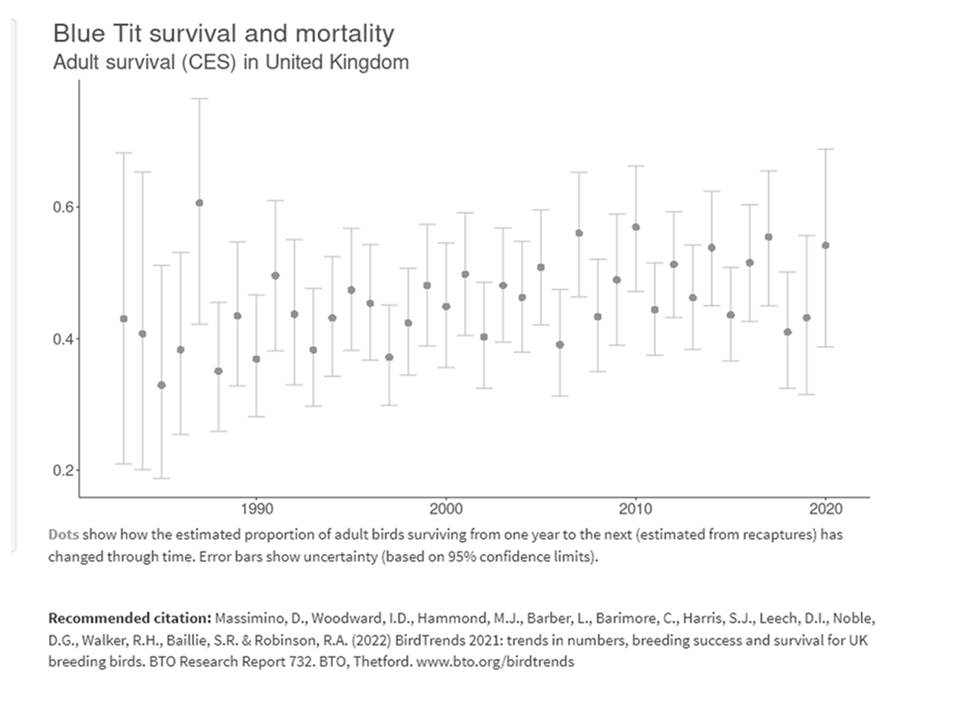

A typical Blue Tit lifespan is three years and they breed at one year old; this plot was constructed by the BTO from ringed bird recovery data and indicates a roughly fifty-fifty chance of a Blue Tit making it from one year to the next. Backwoodsman does not get statistics (having failed it at university) and would probably treat this set of points by putting a trendline through them, indicating that perhaps Blue Tits were revelling in a slightly higher chance of survival with each passing year.

In natural settings, Blue Tits nest in tree holes and lay an average of of eight to ten eggs once, sometimes twice, a year. There are around three million territories in the UK. Around here, any sort of crevice seems to be considered as a potential nest site. I imagine they are very broad-minded when it comes to nesting material – this pair look like they were gathering down for a lining.

The RSPB services and monitors a considerable number of nest boxes in the Kelvingrove Park and Blue Tits are adept at using them – this individual was prospecting in January.

We have always thought that pairs of birds visit us through the winter and it appears that even though their lives are short, mate retention does represent their main breeding strategy.

Come the early summer, we start to get the fledglings, with the Birch sapling turning into a daytime creche and feeding station. The young become independent rapidly and then the cage feeder becomes very busy. Of the eight young that visit just now, four may make it through to breed next year; if our established pairs survive, next year could be very busy. Backwoodsman hopes so.